I sign up to new and interesting social web apps and networks a lot. It’s a strange hobby of mine and I’m not quite sure how I’ve ended up with it. I’ve lost count of how many profiles I’ve created to which service, so I’ve actually discovered forgotten sites by simply googling up my own name. Luckily I don’t usually bother my friends with invitation spam from these services, rather I just like to observe how their general user adoption grows and analyze the design behind a successful service with a sticky user experience if I come across one.

Anyway, I though I’d highlight a few examples of a more recent trend that’s becoming visible in the world of social web. It’s always been about telling the apps what you are doing, thinking or liking, where about and how. Now, after feeding the networks with data about yourself, they are gradually becoming smart enough to tell you what you are like.

Where Do You Go?

Foursquare is not new, but here ‘s a very quick recap: you pull out your mobile phone, launch the app and see what venues are close to you (based on mobile network location data, or GPS for the hifi geeks). You click to check-in to the place you are currently. The end.

Ok, so of course you can also view where your friends have been checking in to. That is, if any of them would be similar gadget geeks like you. I’m pretty sure eventually the location information will become a natural part of the social fabric (waiting for FB Places to arrive here in Finland), but as of now, in reality it isn’t for everyone yet.

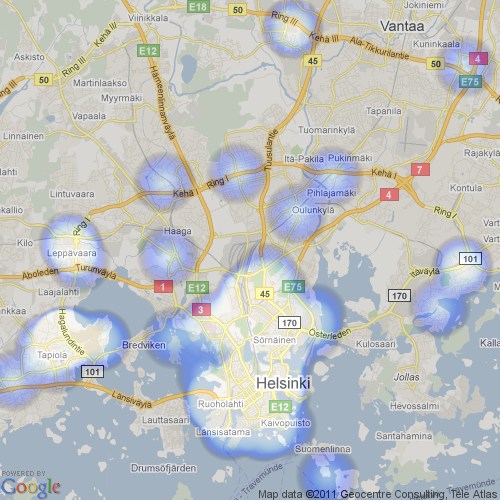

What can you get from the location data then? For example, this heatmap of where I’ve been checking in around the city of Helsinki. Sure, I don’t spend all my time with a finger on the check-in button, nor do the public venues available on the service give an accurate view of where I spend my time. Still, it would be foolish to say that the heatmap doesn’t give me insight on the locations that are a part of my ‘graph in the geographic sense. With enough data and the right presentation method, casual transactions can start to accumulate a whole new value added.

Take a trip down Memolane

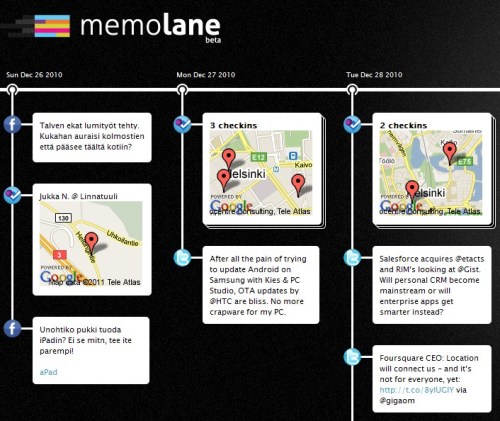

Pretty much every social app has a timeline view of some kind, similar to the FB wall. It’s sort of a divider between generations of applications, as many of the oldskool software and business applicatios are perfectly happy with asking you the user to punch in more and more data without trying to present it back to the users in any aggregated “what’s been happening lately” view. Another common dilemma is that it’s hard if not impossible to automatically combine data from different applications. That’s how bad life used to be only a few years ago.

Integration in the cloud is as easy as OAuth (open authorization), so in a matter of a few clicks you can be connecting the various dots fragmented around your networks into a single stream of information about yourself. Now all there’s left to do is to put a nice timeline UI on top of the data and you’ve got Memolane. Your tweets, check-ins, FB posts, Last.fm scrobbles and everything else in a chronological order that allows you to travel back in time and reminisce about what you did last summer. Yes, again the web knows what you’ve long since forgotten in your selective human brain.

Get Glue’d to the media around you

Apps on top of apps – that’s the future we’re already living in. Why keep on re-inventing the wheel when you could be focusing on designing the rest of the vehicle instead?

Back when Last.fm launched their audioscrobbler app in 2003 the concept of sharing playlist data right from your WinAmp in real time to a web-based service was very novel. Keep in mind, this was waaaay before social networks made sharing and liking and retweeting something that’s considered an everyday activity. I kept on accumulating information their database on a regular basis, then stopped using them, then returned back to an active user thanks to their integration with Spotify.

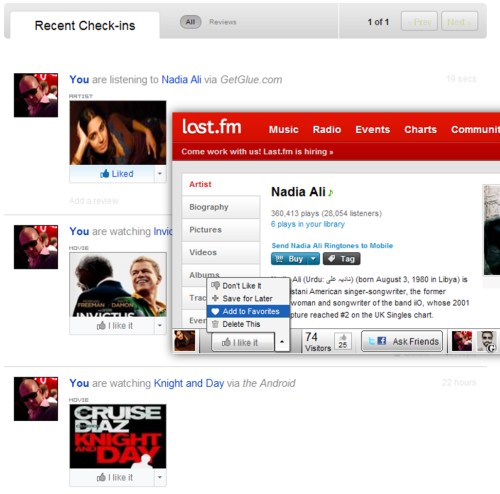

The concept of scrobbling remains cool, but in this day & age there are people out there who cannot be satisfied by merely sharing what track they are listening to. Enter GetGlue. What they’ve built is an almost universal system for checking in to things. Books, movies,TV shows, games, gadgets, restaurants etc. By installing an add-on for your browser and browsing one of hundreds of supported sites that GetGlue recognizes as having content items that their database tracks, you’ll see a toolbar at the bottom of the window. The toolbar not only allow you to like/unlike/favorite/saveforlater or share to FB/Twitter, but it also shows who else has been liking the content in question + recommendations of what else you might like, based on the user data similarity.

Sitting home alone on your sofa and watching Dexter doesn’t have to be unsocial time anymore. Reach for your smartphone, launch the GetGlue app and do a check-in. You’ll see who else has checked into the same show, so you can go and spy their profile to see where their remote has taken them next. While at it, why not do a check-in to that bottle of wine you’ve been sipping? Come on, you’ll get badges as a reward as well!

Sitting home alone on your sofa and watching Dexter doesn’t have to be unsocial time anymore. Reach for your smartphone, launch the GetGlue app and do a check-in. You’ll see who else has checked into the same show, so you can go and spy their profile to see where their remote has taken them next. While at it, why not do a check-in to that bottle of wine you’ve been sipping? Come on, you’ll get badges as a reward as well!

OMG, where’s my privacy?!?

The first reaction from a casual web surfer on all of the new ways in which you can expose yourself to the world will surely be a cry for privacy. Isn’t this the kind of a surveilance society that George Orwell warned us about by writing the 1984? Only it’s worse, since the innocent web surfers have been brainwashed to report back to big brother seemingly on their own free will, just by giving them pictures of digital badges! Someone please stop this insanity!

The first reaction from a casual web surfer on all of the new ways in which you can expose yourself to the world will surely be a cry for privacy. Isn’t this the kind of a surveilance society that George Orwell warned us about by writing the 1984? Only it’s worse, since the innocent web surfers have been brainwashed to report back to big brother seemingly on their own free will, just by giving them pictures of digital badges! Someone please stop this insanity!

I’m going to let you in on a little secret that explains why the situation is not quite that grim at all:

The web knows you because we are the web.

Back in the 90’s, the world wide web was born as a network of documents. Today it is a network of people. Small but profound difference. While it is still perfectly possible for anyone to choose to use the web as a big document management system and just passively consume content that is published there by large organizations and media entities, there is an increasing amount of benefits to be gained by being an active participant instead. Once you cross that line, you start to exist in the web. It may be behind a number of aliases and alter egos, or it may be with your real name and identity (probably both). You may exist in different forms and footprints to anonymous surfers, identified users and verified friends or co-workers. Nevertheless, your actions become a small but integrated part of the fabric of web. Just like you’re a tiny little piece of society, still making an impact all the same.

The web knows you’ve clicked. Google knows you’ve searched. Your ISP knows you’ve downloaded, so don’t waste too much energy on worrying about leaving a trail of what you do when using a networked system like the web. A more interesting question to focus on is how much more can you know about yourself with the help of the web and what value could be derived from the data that you and other fellow citizens of the web are capable of feeding into it. As long as the publishing of data is done through a conscious decision and you pay attention to where the line of privacy is set, it’s hardly any more reckless behaviour than using the web in the old document oriented way. Same old channel, just a very different application.

Mobile phones brought us the concept of electronic phone books, with SIM cards as the media used for transferring these from one device to another. Email client applications like Eudora and Outlook Express gave us the option to store email addresses as contacts in their own address books. Pretty soon the phones began to connect with your PC through a cable and handy software like Nokia PC Suite (don’t get me started on that one…). This meant you now had the problem of several mismatching address books on your computer, so the whole contact management concept started to become painful not just for corporations but private persons as well.

Mobile phones brought us the concept of electronic phone books, with SIM cards as the media used for transferring these from one device to another. Email client applications like Eudora and Outlook Express gave us the option to store email addresses as contacts in their own address books. Pretty soon the phones began to connect with your PC through a cable and handy software like Nokia PC Suite (don’t get me started on that one…). This meant you now had the problem of several mismatching address books on your computer, so the whole contact management concept started to become painful not just for corporations but private persons as well.